South End History:

Table of Contents:

Introduction

Today, Boston’s South End neighborhood is known for its Victorian row houses and parks and is bordered by the Back Bay, Chinatown, and Roxbury. Before the 17th century, however, it was a tidal marsh used by the indigenous Massachusett people as fishing and hunting grounds which contributed to a vital regional trade network. English settlers arrived in the early 17th century, destabilizing the area’s Native communities with the spread of foreign disease, violent armed conflict, and land seizure.

From the 18th to the 19th centuries, Boston grew into the region’s major economic center due to increased maritime trade and booming industry, which reached as far as the Indian Ocean and China. As Boston’s economic footprint grew, people flocked to the city, drawn by economic opportunity; many of these new residents were immigrants. To accommodate the city's population boom, many neighborhoods, including the South End, underwent landmaking projects in which the surrounding tidal marshes were filled.

Through the second half of the 19th century, the South End became home to an increasing number of immigrants, including Eastern European Jews, Irish, Syrians, Greeks, and Armenians. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the neighborhood drew immigrants from Jamaica, Barbados, and Montserrat as well as African American migrants seeking to escape the Jim Crow laws rampant in the American South.

People on a street corner in the South End United South End Settlements, Northeastern University Library Archives and Special Collections. http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20452172.

The South End in the 20th century witnessed the growth of a number of advocacy organizations. The NAACP established its Boston branch there, and several settlement houses and grass-roots organizations advocating for the rights of women and racial minorities were established, including the Harriet Tubman House. In the mid-to-late-20th century, the South End was reshaped by discriminatory housing policies and urban renewal, which displaced thousands of residents from their homes. Today, the South End continues to feel the reverberations of these policies, in part through gentrification, or the process of changing the character of a historically poor urban neighborhood for the benefit of new and wealthy residents.

Shawmut: 12,000 BP[1]- 1630 C.E.

Before the arrival of European settlers, the place we know now as Boston was called Shawmut; this land is part of the ancestral territory of the Massachusett people, who have lived here for thousands of years and continue to inhabit these lands today. The Colony of Massachusetts—and later, the Province and the Commonwealth—took their name from the tribe of indigenous peoples who lived and thrived on these lands. Starting around 12,000 BP, Native people settled in the region. Although no artifacts found in Boston date to this earliest time, stone tools have been found in surrounding towns such as Saugus, Watertown, and Canton, hinting at the presence of people in and around Boston. Artifacts such as stone tools and fish weirs provide hard evidence that the Shawmut Peninsula was inhabited and fished some 7,500 years before present.[2]

The geography of this land has changed drastically in the last 400-odd years. Prior to colonization and 19th-century landmaking projects, the Shawmut Peninsula was connected to the mainland by a narrow isthmus that English settlers termed Boston Neck. What is today the South End was then composed of mudflats: silty tidal marshes that were submerged at high tide and exposed at low tide. The Massachusett and their forebears relied on these tidal flats as fishing and hunting grounds, which were also a vital part of a regional trade network that linked the Wampanoag and Pequot tribes to the south and west, and the Nipmuck and Abenaki tribes to the north.[3] Thousands, if not millions, of people, lived in and around what is now Boston, settling in villages located at the mouths of rivers and along the coast.[4]

Boston: From Puritan Colony to City of Immigrants

Although the Puritan settlement of Boston was not formally established until 1630, Native communities had extensive trade contact with English, French, and Dutch traders throughout much of the 16th and early 17th centuries. At some point between 1617 and 1619, a European ship brought an epidemic ashore, most likely smallpox. The Massachusett population was devastated; by the time of the Mayflower’s arrival in 1620, entire villages had been eradicated. Although the region's Native peoples resisted the invasion of English settlers, many thousands were killed by further foreign disease outbreaks and violent armed conflict. Subsequently, long-held trade relationships and foodways were destabilized, and most of their ancestral lands were stolen through acts of war and unfair or broken treaties.[5]

Over the course of the 18th century, Boston—strategically situated in Boston Harbor—became the epicenter of the region’s maritime economy. In the years following the American Revolution, economic relations between Britain and the fledgling nation were strained, and Boston merchants found commercial partners in other parts of the globe, most notably China. This maritime trade network came to be known as the China Trade; Boston played a central role in the exchange of American furs, Turkish opium, Chinese tea, silks, porcelain, and spices. Sparked by this economic boom, Boston’s population nearly doubled between 1790 and 1810.[6]

As the 19th century progressed, Boston evolved into a center of industry: as shoe and textile industries flourished in Massachusetts, the invention of the railroad connected Boston to industrial towns across the region. At the same time, the city’s maritime trade continued to grow; traders and missionaries traversed the globe, establishing relationships that many immigrants would follow back to Boston. From 1820 to 1880, Boston’s population grew more than eightfold, and the 1880 Census documented more than 114,000 immigrants or nearly a third of the city’s population.[7]

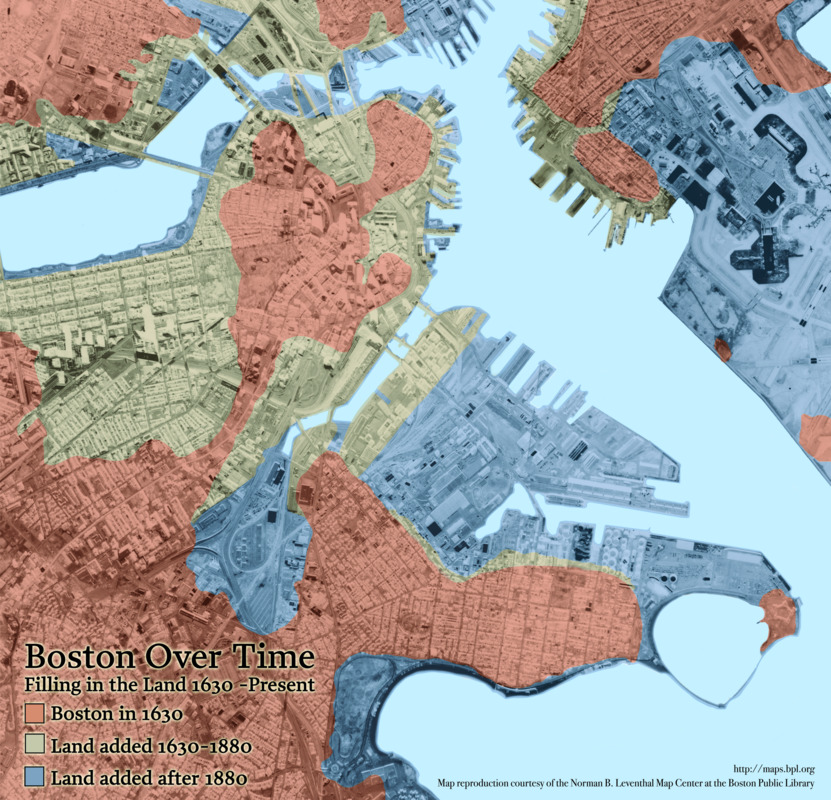

Making the South End

It quickly became apparent that the existing peninsula could not accommodate Boston’s rapid population growth, much less the railroad depots and commercial facilities needed to support the growing city. The result was a flurry of landmaking projects, in which people built out into the tidal marshes surrounding the peninsula, filling in the muddy flats with sand, gravel, mud, and trash, typically stopping just above the high tide line.[8] This activity continued well into the 20th century. Today, about ⅙ of Boston rests on made land; this includes the South End.

As immigrants found shelter and community in tenement housing, the city’s middle- and upper-class white, Yankee, and Protestant families increasingly retreated to the suburbs. The Back Bay and South End neighborhoods, both developed on newly made land in the mid-to-late-19th centuries, were intended to halt this exodus. However, developers struggled to entice wealthy residents to buy property in the South End; construction was slow but still outpaced the demand for high-end townhouses. As early as the 1860s, a pattern emerged: some wealthy residents, mainly merchants, bought property along the neighborhood’s garden squares; middle-class property owners largely rented out apartments to lodgers in the surrounding blocks, and the streets most distant from the green spaces were inhabited mainly by renters in lodging houses and tenements.[9]

Chan Krieger & Associates. "Boston Over Time." Map. 2008. Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:q524n559t (accessed October 20, 2021).

Twin financial crises for the city further fatigued the neighborhood’s real estate market. The Great Fire of 1872 proved to be the most destructive fire in the city’s history. For more than fifteen hours, the fire raged through Boston’s commercial district, a 65-acre area bound by Washington, Summer, and Milk Streets and the waterfront. The conflagration destroyed 776 buildings, caused around $73.5 million in damages (over $1.5 billion in today's dollars), and cost approximately 30 people their lives. The loss of nearly 1,000 businesses had dire ramifications for residents of the South End, many of whom were merchants and laborers who chose the neighborhood for the easy commute to the commercial district.[10] A few months later, the Financial Panic of 1873 brought about the first global Great Depression brought about by industrial capitalism. All industrial nations felt the impact of this economic downturn; stock markets, financial institutions, and railroad companies collapsed. Locally, banks foreclosed on buildings in the South End; some scholars believe that this caused a spread of defaults, tipping the neighborhood into poverty.[11]

Immigrant Communities in the South End

In the mid-19th century, the South End was settled largely by the native-born middle-class, along with a small population of Irish and German immigrants. But as property values in the South End continued to decline, the fabric of the neighborhood began to shift: lodging houses and tenements multiplied, attracting a mix of young single people and immigrant families.[12] Over the latter half of the century, Anglo-Canadians, British, and native-born Americans emigrating from rural New England arrived in the neighborhood.[13]

In the mid-19th century, a small number of Jewish immigrants from Germany and Poland settled in the South End. Between the 1880s and the turn of the 20th century, a larger wave of Jewish immigrants arrived from central Europe and the Russian Pale of Settlement. These newcomers settled in the New York Streets, an area in the northeast corner of the neighborhood.[14] The enclave was so named when its streets were named for cities and towns in New York to celebrate the completion of the railroad linking Boston and Albany in 1842.[15] In the late 19th and early 20th century, a number of southern Italians moved from the North End to the South End, settling alongside their Jewish neighbors in the New York Streets.[16] Many residents of the New York Streets worked in factories, steam laundries, or in the docks and railroads south of Washington Street; others opened ethnic bakeries, groceries, and specialty stores.[17]

In the 1890s a wave of male immigrants from Syria, Greece, and Armenia settled in the nearby Chinatown and South Cove neighborhoods, where many of them found work peddling fabric, notions, and other goods. After World War I, many of these men brought their families to join them and relocated in the South End, where they opened shops, bakeries, groceries, and restaurants; many also opened lodging houses.[18]

In the late 19th century, the South End also drew Black migrants from the American South and immigrants from Jamaica, Barbados, and Montserrat. Unwelcome in Boston’s predominantly white Episcopalian churches, the South End’s West Indian congregants established St. Cyprian’s Church.[19] By the turn of the century, the South End had become Boston’s new hub of Black community, culture, and political life. Between 1916 and 1970, prompted by poor economic conditions and racial oppression in the Jim Crow South, an estimated six million Black Americans relocated from the rural South to urban centers in the Northeast and Midwest. Known as the Great Migration, this movement brought thousands of emigrants to Boston: between 1900 and 1950, the city’s Black population had grown fourfold, to 51,568 people out of a total population of 801,444. The majority of these new Bostonians settled in the South End, Lower Roxbury, and, in the 1930s, expanded into Roxbury.[20]

As Boston’s rapid industrialization attracted greater numbers of new residents, middle-class urban reformers advocated for improved social and living conditions for those living in poverty. Settlement houses were one such embodiment of the reformist movement. These institutions were staffed by volunteer middle-class “settlers” or “residents” who lived in poor urban areas with the purpose of assimilating their immigrant neighbors through example and education.[22] Settlement houses offered daycare services, educational programming, healthcare, and other social services. But many settlement houses excluded Black residents, either refusing service entirely or offering segregated programs.[23]

In the years following the Second World War, Puerto Ricans and Dominicans settled in the South End, as well as in Roxbury and Dorchester. By 1950, the South End had become the heart of the city’s Latine community. By the 1960s, 2,000 Puerto Ricans lived in the area bound by West Newton, West Dedham, Tremont, and Washington streets.[24] Many found work in the service and industrial sectors, and many others who resided in Boston traveled around the state as seasonal farm laborers; women frequently worked in domestic service or ran boarding houses.[25]

By the late 1960s, the South End’s Black and Puerto Rican residents led the community fight against displacement to urban renewal. Years of community organizing and struggle led by grassroots organizations resulted in a new model of citizen participation in urban renewal; Inquilinos Boricuas en Acción ("Puerto Rican Tenants in Action", or IBA) won the right to sponsor and develop the urban renewal plot that had been slated to displace thousands of residents in the South End’s Puerto Rican neighborhood. Instead, IBA developed Villa Victoria, a housing community that today contains more than 600 affordable housing units and is home to some 900 households. Villa Victoria also includes public and commercial space and operates a daycare center, economic development programs, an arts program, a technology center, and programming for older adults.[26]

Black History in the South End

In the early 19th century, the north slope of Beacon Hill was the center of Boston’s free Black community; many Black residents also settled in the city’s West End neighborhood. Led by the Beacon Hill community, Boston had been a center of abolitionist activity, and by the end of the century, Massachusetts had enacted some of the strongest civil rights legislation in the nation. In 1880, restrictions on Black property ownership were loosened, allowing Black Bostonians to gain upward mobility as homeowners.[27] At the same time, European immigrants began settling in the West End and Beacon Hill neighborhoods, prompting upwardly mobile Black residents to purchase row houses in the South End and Roxbury.[28] Homeownership provided some stability for Black Bostonians, and notably for Black women, many of whom fostered independent wealth by owning and operating rooming houses in the South End.[29]

However, Jim Crow laws increasingly enforced racial segregation throughout the U.S. and Boston was no exception. Both formal and informal policies of white supremacy and racial segregation, undergirded by violence, expelled Black residents from most Boston neighborhoods. The South End remained open to Black Bostonians and became one of the city’s most racially and ethnically diverse neighborhoods. Black emigrants from the American South and immigrants from the West Indies also found community in the South End. By the 1890s, the South End had become Boston’s new center of Black community, culture, and politics. Black South Enders responded to the city’s segregation of public spaces by establishing their own theaters, venues, restaurants, unions, social clubs, religious institutions, lodging places, and settlement houses.[30]

Original Harriet Tubman House, 25-27 Holyoke St, Northeastern University Library, Archives and Special Collections. http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20452196 (accessed August 8, 2023).

One such example is the Harriet Tubman House. Like most philanthropic reform organizations of the time, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was segregated; the Black arm of this temperance organization was known as the Harriet Tubman branch of the WCTU, named for the famed abolitionist and activist; some sources have referred to its members as the Harriet Tubman Crusaders.[31] In 1904, under the leadership of Jula O. Henson, this group founded the Harriet Tubman House on Holyoke St. as a residence for single Black women who emigrated to Boston from the South, seeking work or education. The organization quickly grew into a vital community institution and expanded its services to include career placement and youth programs. A personal friend of Harriet Tubman, Henson donated her own townhome at 25 Holyoke Street to serve as the organization’s headquarters. The Harriet Tubman House served as Boston’s only autonomous space created and run for Black women until after World War I.[32]

The Harriet Tubman House paved the way for local groups, led by Black women organizers, to shelter, empower, and serve Black women workers, migrants, and students who were systemically marginalized from white-led service agencies and lodging houses due to racist policies. One such group was the Women's Service Club (WSC), whose history is also closely tied with that of the Boston branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

In 1911, the NAACP held its second annual meeting in Boston; the following year, the Boston Branch received its charter, marking it as the first chartered branch of the NAACP and the city’s oldest and largest volunteer-run civil rights organization devoted to ending racial discrimination.[33] The branch’s founding members included Julia Henson, along with activist Mary Evans Wilson and her husband, civil rights attorney Butler R. Wilson. While Butler Wilson would become the branch’s first secretary, and later president, Mary Evans Wilson was a prolific organizer in her own right. She recruited thousands of members to the branch; in 1917, she organized a knitting circle to provide warm clothing to soldiers of color and attract participants to the NAACP. In 1919, this knitting club officially became incorporated as the Women’s Service Club of Boston. Along with the Harriet Tubman House, the WSC would go on to expand its services to provide men, women, and children with basic necessities, vocational instruction, and job placement services.[34]

The Boston Branch of the NAACP was headquartered at 451 Massachusetts Avenue, on the corner of Columbus Avenue, until the office relocated to Roxbury after falling victim to foreclosure in 1995.[35] During this time, the branch pushed for the passage of federal anti-lynching legislation and brought numerous historic lawsuits against the City of Boston. Combined with sit-ins, marches, and other actions, these lawsuits paved the way for the desegregation of schools, housing developments, and the Boston Police and Fire Departments. In December 1975, two firebombings occurred at the Boston Branch headquarters on Massachusetts Avenue. This attack was suspected of being a violent response to Boston’s court-ordered efforts to desegregate schools by busing students between neighborhoods. The busing initiative had rolled out during the 1974-1975 school year; the day prior to the bombing, South Boston High School had been placed into receivership for failing to follow desegregation orders[36]. Boston’s Black community demanded an immediate investigation and that those responsible be held accountable. Investigations began shortly after the attack; however, there was little media coverage and the case seemingly went unsolved.[37] Today, the Boston Branch of the NAACP is among the largest in New England and continues to advocate for racial justice.[38]

Between 1916 and 1970, an estimated six million Black Americans relocated from the rural South to urban centers in the Northeast and Midwest, prompted by poor economic conditions and racial oppression in the Jim Crow South. This mass exodus, known as the Great Migration, brought thousands of emigrants to Boston: in 1900, the city’s Black population numbered 11,591 people, out of a total city population of 560,892; by 1950, this number had grown to 51,568 people out of 801,444.[39] This growing population also included newer immigrants from the West Indies, particularly Barbados and Jamaica; these new Bostonians settled in the South End, Lower Roxbury, and, in the 1930s, expanded into Roxbury.[40] The South End’s Crosstown area—the neighborhood’s center, at the intersection of Columbus Avenue and Massachusetts Avenue—was the nucleus of Boston’s Black community and commerce.[41] It was also the epicenter of Boston’s Black entertainment and nightlife; during his nightly broadcasts at the Hi-Hat, disc jockey Symphony Sid Torin named the intersection of Massachusetts and Columbus “the Jazz Corner of Boston.”[42] The neighborhood was dense with nightclubs, lounges, theaters, and ballrooms, and while most of these venues were white-owned, many were integrated and offered opportunities for Black entertainers and entrepreneurs.[43]

Prior to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, racial discrimination was widespread and, in many parts of the country, legally prescribed in schools, housing, hospitals, transportation, public accommodations, and workplaces. Throughout the Jim Crow era, most hotels, restaurants, and entertainment venues in Boston excluded Black patrons. Many Black jazz musicians–touring and locals alike–instead found accommodations in the South End’s abundant rooming houses and private homes. Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie, J. C. Higginbotham, Clark Terry, Wardell Gray, Russell Jacquet, Fat Man Robinson, Percy Heath, Milt Jackson, and many other jazz greats performed and stayed in the South End. Sammy Davis Jr. stayed in so many different places during his frequent stops in Boston during the 1930s and 1940s that neighborhood residents made a game of speculating as to where he’d be spotted. Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, and Duke Ellington frequently dined and rehearsed at Mother’s Lunch, a restaurant, venue, and boarding house located at 510 Columbus Ave and run by Wilhelmina “Mother” Garnes until its closure in 1956.[44]

Martin Luther King, Jr. resided in a boarding house a few doors down at 397 Massachusetts Ave. while studying theology at Boston University.[45] King moved to Boston from 1951 to 1954 to pursue his doctorate at Boston University School of Theology. During this time, he met Coretta Scott, who was completing her degree in music education in Boston, and the two married in 1953. King returned to Boston on many occasions, most notably in April 1965 to lead a march from Carter Playground in Roxbury to Boston Common, speaking out against segregation in schools and high rates of unemployment.[46]

Phyllis M. Ryan, Dr. Martin Luther King meeting with local politicians, including Massachusetts Governor John A. Volpe, April 1965. http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20249047.

The Pioneer Social Club was located on Westfield Street, a couple of blocks from the major intersection at Columbus and Massachusetts Avenues. The private club, owned by brothers Balcom and Silas “Shag” Taylor, became known as a legendary jazz venue. Unlike most venues in Boston, the Pioneer Club was both Black-owned and integrated. Jazz greats were known to frequent and perform here, including Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Erroll Garner, Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, Sarah Vaughan, and Sonny Stitt. At a time when there were no elected Black officials in city or state government, the Taylor brothers were among Boston’s most powerful political figures; Shag Taylor was nicknamed “the Mayor of Roxbury.” The Taylors would rally support for Democratic candidates in the city’s majority-Black wards; in turn, they were granted political favors and leniency regarding the nightclub’s late-night activities. With their influence extending across Roxbury and the South End, they championed voting rights, political participation, fair housing, and jobs for the city’s Black constituents.[47]

The Hi-Hat, located at 572 Columbus Avenue (on the plot of land that would later become the Harriet Tubman House at 566 Columbus Avenue), was the most famous and celebrated of the South End’s jazz clubs, and one of the most significant in New England’s jazz history. The Hi-Hat opened as a restaurant and nightclub in 1937 and became a jazz venue in 1948. From that point until its closure due to a fire in 1955, the Hi-Hat was Boston’s most significant jazz incubator. It was the first club in Boston to present as bandleaders Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Erroll Garner, Miles Davis, Oscar Peterson, and Thelonius Monk. It was also the city’s first club to present as headliners Carmen McRae, Jeri Southern, Ruth Brown, and Sarah Vaughan. Dozens of Boston musicians worked there, including Al Vega, Bernie Griggs, Charlie Mariano, Clarence Jackson, Dean Earl, Fat Man Robinson, Hillary Rose, Jimmy Tyler, Nat Pierce, Rollins Griffith, Sabby Lewis, and many others.[48] Many of the jazz musicians who performed at the Hi-Hat were depicted in Jameel Parker's "Honor Roll" mural, installed in 1999 on the facade of the Harriet Tubman House.

Bruce Myren, Harriet Tubman House The Honor Roll Mural on Massachusetts Avenue, 2020. Northeastern University Archives & Special Collections, http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20418919.

Bruce Myren, Harriet Tubman House The Honor Roll Mural on Columbus Avenue, 2020. Northeastern University Archives & Special Collections, http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20418917.

The Hi-Hat was one of several jazz clubs situated along Columbus Avenue in Boston’s South End, an area that has been dubbed as Boston’s "mecca for jazz."[49] Across the street from The Hi-Hat was Wally's Jazz Café, another jazz club that has withstood many of the South End's changes. It was founded in 1947 by Joseph "Wally" Walcott, who was the first Black man to own a nightclub in New England. Wally's Jazz Café attracted both student and professional jazz musicians and allowed them to gain audiences, connections, and experience.[50] In 2020, the club temporarily closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but after successful community fundraising, the club reopened in September 2022.[51]

Hall, Winifred I. An unidentified band performs at the Hi-Hat, ca. 1935-1944. Northeastern University Archives & Special Collections, http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20197287.

For much of the 20th century, the American Federation of Musicians (AFM) was racially segregated with Local 9 representing white musicians, and Local 535 representing Black musicians. Local 9 members dominated the hotel ballrooms and theaters, Local 535’s members played the jazz circuit in the South End and downtown clubs. In 1970, the AFM directed the merger of Locals 9 and 535; today, Boston’s professional musicians are represented by Local 9-535.[52]

Local 535 was not the only Black-led labor union headquartered in the neighborhood. The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) met regularly in a room above Charlie’s Sandwich Shoppe at 429 Columbus Avenue. Founded by the civil rights pioneer A. Philip Randolph, the BSCP would go on to become one of the country’s most powerful all-Black working-class organizations.[53]

The Dining Car Waiters Local 370, affiliated with the Hotel and Restaurant Union and the AFL-CIO, claimed even more Boston members than the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. In the years following World War II, the Local 370 fought to raise waiters’ salaries and desegregate cafeteria cars, and successfully filed one of the first cases with the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination.[54] Like the Brotherhood, the Local 370 was based in the South End; the union hall was at 10 Yarmouth Street, a side street along Columbus Avenue and a short walk from the Brotherhood’s meeting place above Charlie’s.[55]

Redlining

In 1933, Congress passed the Home Owners Loan Act as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal; this act provided emergency mortgage assistance to homeowners and would-be homeowners by providing loans or refinancing mortgages. It also created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), the body that refinanced loans with extended repayment schedules and low-interest rates, allowing working- and middle-class families to secure property and build wealth. However, HOLC evaluated all metropolitan areas in the country to assess the risk of insuring mortgages. The agency did this by hiring local real estate professionals–lenders, developers, and real estate appraisers–to make appraisals, determining how HOLC would reach refinancing decisions.

While HOLC agents considered factors like proximity to utilities, age and quality of homes, and economic class of residents, the risk of investment was largely determined by neighborhood demographics. Using this data, HOLC created color-coded maps of every metropolitan area in the country. White, affluent neighborhoods were deemed the “best” investments for banks and other mortgage lenders; they received a grade of ‘A’ and were colored green on these maps. Neighborhoods that were considered “still desirable” were graded ‘B’ and shaded in blue; residents of these neighborhoods were almost always white and U.S.-born, and these areas were still considered sound investments. Neighborhoods inhabited by working-class communities and/or immigrants were appraised as “declining” and received a grade of ‘C’; they often lacked easy access to amenities and were indicated in yellow on the maps. Those “infiltrated” by immigrants and people of color were considered “hazardous” investments; they were graded ‘D’ and colored red. A neighborhood inhabited by Black people was designated red, regardless of the economic class of its residents; Boston’s South End was one such neighborhood. Residents of these “hazardous” neighborhoods found it difficult or nearly impossible to secure loans or mortgages. Thus, this process came to be known as redlining. This state-sanctioned racial discrimination cultivated a cycle of disinvestment in redlined neighborhoods, preventing residents from owning homes and building generational wealth.[56]

Home Owners' Loan Corporation and George F. Cram Company, “Residential security map of Boston, Mass.,” 1938, Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:00000x52b (accessed January 05, 2022).

The National Housing Act was enacted the following year to make housing and home mortgages more affordable to middle-class renters. The Housing Act is widely credited with alleviating the housing crisis during the Great Depression, but almost exclusively to the benefit of white homeowners. The Act created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which insured bank mortgages, incentivizing lenders to offer more mortgages to more people. However, like HOLC, the FHA conducted property appraisals to ensure that any such loans were low-risk. The agency’s appraisal standards included an explicit whites-only requirement, preventing people of color from buying homes in majority white suburban neighborhoods, further codifying segregationist housing practices, and actively disinvesting in Black neighborhoods.[57]

These systemic, discriminatory housing policies are examples of de jure segregation, or racially explicit laws and policies enacted by federal, state, and local governments that determined where white and Black people could live. Both redlining and the FHA loan appraisals ensured that racially and ethnically diverse neighborhoods, and particularly Black communities, faced massive barriers to accessing capital investments. Redlining created or reinforced racial and economic divisions that persist in most metropolitan areas today: 74% of the neighborhoods graded as high-risk or “hazardous” in the 1930s are low-to-moderate income neighborhoods today, and 64% of these “hazardous” neighborhoods are now majority-minority neighborhoods.[58]

Urban Renewal

By channeling investments away from ethnic and racial minority communities in cities, redlining ensured the economic decline of these neighborhoods, paving the way for urban renewal and later gentrification. Established by the American Housing Act of 1949, urban renewal was a federally funded program in which local governments seized and demolished public and private properties for the purpose of renovating or replacing housing or public works considered substandard.[59] Although urban renewal aimed to raise land values in urban areas, the program allowed cities to clear "blighted" land–a euphemism that disproportionately targeted low-income, minority neighborhoods. For a quarter of a century, urban renewal displaced hundreds of thousands of families across tens of thousands of acres across the country, replacing tight-knit communities with highways, modernist apartment blocks, or industrial centers. And while the federal program was supposed to compensate displaced people or provide logistical assistance in their relocation (to crowded, segregated housing), this support was frequently late in coming or never arrived at all. Often, local urban renewal administrators never compensated displaced families for the fair market value for seized properties, robbing them of generational wealth.[60]

Courtesy of United South End Settlements. Demolition Crews during the construction of the Mass Pike. Northeastern University Archives & Special Collections, http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20452199.

The redlining of neighborhoods and the urban renewal construction of racially segregated public housing not only ensured housing segregation; these practices also ensured that neighborhood schools remained segregated. In the 1950s, 80% of Boston’s Black elementary school students attended majority-Black schools, which were overcrowded, under-resourced, and understaffed. Across the Boston Public School system, per-student spending averaged $340 for white students compared with $240 for Black students.[61] In 1974, a federal court issued the Morgan v. Hannigan decision, ordering the desegregation of schools via busing. Students were transported on buses to schools often further away from their homes in an effort to curb schools’ racial imbalance, resulting in violent retaliation from many white residents.[62]

Boston Housing Authority, Southwesterly from Corner of Way and Harrison Avenue, August 24, 1955, Photograph, August 24, 1955, Boston City Archives Digital Records Portal, https://cityofboston.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_61c73812-1a09-4b50-b32f-9460c693b61c/.

Throughout much of the 20th century, the South End was characterized as one of Boston’s poorest and most ethnically and racially diverse neighborhoods. Prevented by discriminatory policies from securing federal mortgage loans to buy homes, most residents lived in lodging houses. Thanks to redlining, decades of divestment ensured that the neighborhood remained poor; it was subsequently a prime target for urban renewal.

The New York Streets marked the first of Boston’s neighborhoods to succumb to urban renewal. Each street was named for a town along the Erie Canal in celebration of the completion of the Boston and Albany Railroad in 1842. Since the late 19th century, the New York Streets had been home to a tight-knit and ethnically diverse community of some 2,500 people, many of whom were working-class immigrants. Residents lived in rented apartments scattered alongside places of worship, boys and girls clubs, social service providers, shops, small factories, garages, warehouses, bars, and theaters.[63] In the wake of the Federal Housing Act of 1949, the city secured funding to plan the seizure and demolition of the New York Streets; by 1957, 321 buildings were razed and more than 1,000 residents were displaced by new industrial buildings.

In 1957, the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA, the predecessor to today’s Boston Planning and Development Agency, or BPDA) was established as the city enforcer of urban renewal and redevelopment projects.[64]

At the end of 1959, the BRA announced urban renewal plans for the South End’s Castle Square neighborhood, which was home to more than one thousand families. Although the BRA responded to community pushback by adding more affordable housing units to their initial plan of industrial reuse, the available units were far outnumbered by displaced families from multiple urban renewal projects across the city. As demolition loomed, and with the destruction of the New York Streets in recent memory, many families began to retreat from the neighborhood.[65]

In January of 1960, five neighborhood social service agencies–the South End House, Lincoln House, Hale House, Harriet Tubman House, and Children’s Art Centre–incorporated into the United South End Settlements (USES), with strategizing around urban renewal at the core of the new organization’s long-range planning. To this end, one of its first initiatives was to contract with the BRA to relocate displaced residents of Castle Square between 1962 and 1963. Hundreds of volunteers scoured Boston neighborhoods for low-cost rental units, and USES offered home-buying clinics and provided loans and grants to dozens of families. The organization also coordinated with government agencies, local nonprofits, and places of worship to provide residents with social services and furnishings for their new homes. All told, in just a year and a half, 644 displaced people were successfully relocated.[66]

Boston Redevelopment Authority, "South End urban renewal area R-56," map, 1965, Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:7h14cx94p (accessed January 21, 2022).

Boston Housing Authority, Boston Herald Traveler Site from Corner of Broadway and Albany Street, May 23, 1958, Photograph, May 23, 1958, Boston City Archives Digital Records Portal, https://cityofboston.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_fec0506c-3b6b-4228-b72d-68e89422c9f3/.

In Boston and nationwide, Black families and other communities of color were disproportionately displaced by urban renewal. By the late 1960s, at least 10,249 families in Boston had been displaced; approximately one-third of these families were non-white, despite people of color representing about 20% of the overall population. In the South End, more than 3,550 families were forcibly removed from their homes; of these, nearly half were families of color.[67][68] The federal government inconsistently gathered data around urban renewal; the known numbers represent a fraction of the people forcibly removed from their communities. The data gathered leaves out the stories of individual adults, and it is unclear how Boston’s administrators defined “non-white” for the purposes of these reports. Census data shows that between 1950 and 1980, the South End lost 18,152 residents, or just over half of its population.[69]

With their homes and businesses seized by eminent domain, those displaced by urban renewal often experienced economic hardship and the traumatic loss of community. Contemporary scholars posit that urban renewal is to blame for the destruction of communities that served as support networks. This disruption of relationships and social, emotional, and financial resources has a profound ripple effect: displaced individuals experience an erosion of trust, increased stress, and subsequently a higher risk for stress-related ailments, including depression and heart disease.[70]

Organizing against Renewal

Urban renewal sparked a wave of community organizing and activism. In 1965, the BRA adopted the South End Urban Renewal Plan, targeting an area known as Parcel 19 for demolition. Parcel 19 sat in the heart of the South End’s Puerto Rican community. In the South End Urban Renewal Plan, the existing housing would be razed and replaced with housing that residents would be unable to afford; the plan did not include relocation for displaced residents.[71]

Residents and activists–including Israel Feliciano, Rev. William Dwyer, Helen Morton, and Phil Bradley–organized the Inquilinos Boricuas en Acción, Inc. (Puerto Rican Tenants in Action, or IBA). IBA, a grassroots group devoted to empowering residents through safe and sustainable affordable housing, campaigned and organized under the motto "No nos mudaremos de la parcela 19 (We will not be moved from Parcel 19).” In 1969, IBA won the right to sponsor and develop Plot 19. Inspired by the architecture of Puerto Rico, the group developed Villa Victoria, an affordable housing community that today contains 667 units, home to more than 1200 residents.[72] Villa Victoria also includes public and commercial space and operates a daycare center, economic development programs, an arts program, a technology center, and programming for older adults.

Inquilinos Boricuas en Acción, Children Playing on Playground Equipment in the Strip between Two Rows of Villa Victoria Housing, ca. 1970-1980, Photograph, Inquilinos Boricuas en Acción records (M111), Northeastern University Archives & Special Collections, http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20225797.

In 1967, after years of working as a community organizer, anti-poverty activist, and youth outreach director for USES, Mel King founded Community Alliance for a Unified South End (CAUSE) to support the self-advocacy of neighborhood residents facing displacement.[73] In 1968, the BRA demolished housing in a parcel of land on the corner of Columbus and Dartmouth Avenues, displacing one hundred families and replacing them with a parking lot. Shortly thereafter, the BRA announced plans to construct a parking garage on this site. On April 26, under King’s leadership, CAUSE staged a sit-in at the BRA’s South End office; two days later, members of CAUSE occupied the parking lot to call attention to the neighborhood’s need for affordable housing, rather than a parking structure. There, they were joined for the next three days by hundreds of supporters in what a Boston Globe reporter described as a “the atmosphere of a carnival.”[74] The protestors pitched tents and built wooden houses, and installed a large sign inviting passers-by and the press to join them at Tent City; for four days, they shared food, set up a localized mail system, and played music.[75]

Courtesy of Boston Globe Library Collection. Ollie Noonan Jr., “Tent City” Entrance to Parking Lot, April 29, 1968, Photograph, April 29, 1968, Boston Globe Library collection (M214), Northeastern University Archives & Special Collections, https://repository.library.northeastern.edu/files/neu:m0447q24q.

Sympathetic media attention drew public support, but the fight for affordable housing on this site would continue for another twenty years. Within the year following the protest, organizers established the Tent City Task Force; in 1979, it became the Tent City Corporation, a community development organization advocating for the construction of affordable housing on the still-empty parking lot. Finally, after years of advocacy and planning, a coalition of nonprofits, city agencies, and community organizations moved forward with plans to develop the site, and in 1988, the Tent City Housing Complex opened its doors as a mixed-income housing development, resting atop a below-ground parking lot.[76]

In May 1968, inspired by the successes of Villa Victoria and the Tent City actions, a multi-ethnic, multiracial group of some 700 low-income renters formed the South End Tenants’ Council (SETC).[77] Under the leadership of Mary Longley, Mel King, Ted Parrish, and Leon Williams, the group fought Joseph, Raphael, and Israel Mindick, three brothers who managed more than sixty deteriorating buildings in the South End. The SETC documented the hazardous living conditions and filed formal complaints in the city’s municipal courts, which failed to produce timely results. When the SETC organized a rent strike and protested in front of the Mindicks’ homes and synagogue, the Beth Din, or rabbinical court, intervened, marking the first time that a Beth Din considered a case involving a social issue; the court’s role has historically been to adjudicate conflicts and provide guidance within the Jewish community. Jewish law firms and congregations flooded the Beth Din with letters in support of the tenants, and after months of arbitration, an agreement was reached in which the BRA purchased the buildings from the Mindick family and agreed that the tenants themselves would become the owners and redevelopers of their homes.[78]

The following year, the BRA secured funds from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to rehabilitate one hundred buildings, and the SETC established a development subsidiary, the Tenants’ Development Corporation (TDC), to manage the redevelopment project. This made TDC the first tenants’ group in the country to organize and purchase residential buildings with the cooperation and support of HUD.[79]From 2003 until the building’s sale in 2020, TDC’s offices were based in the Harriet Tubman House at 566 Columbus Avenue. Today, TDC remains a Black-owned, tenant-led organization devoted to growing affordable housing and empowering community through educational programming in the South End.[80]

With national support for urban renewal waning, President Gerald Ford signed the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974, which phased out federal urban renewal funding, instead offering block grants that afforded local officials and communities greater decision-making power around development projects.[81]

The South End’s Queer History

By the mid-20th century, Boston’s queer community began to grow and gain visibility. At home and abroad, the Second World War had propelled tremendous social change: enlistment and new employment opportunities–whether in military production, government offices, or healthcare–accelerated a massive movement of people into overwhelmingly gender-segregated environments.[82] These new social spaces, framed by the strain of war, fostered physical and emotional intimacy and allowed an unknown number of individuals to explore non-heterosexual attractions and develop meaningful same-sex relationships on an unprecedented scale.[83]

After returning from their respective war efforts, people flocked to urban areas. In comparison to smaller towns and rural areas, cities like Boston provided relative anonymity, privacy, and independence in which a growing community of young queer people could explore their sexualities and gender expressions. The abundance of colleges and universities offered a socially acceptable means of leaving home and finding community.[84] In the South End, same-sex rooming houses catering to single people abounded, providing shelter and acceptable social cover for queer people to live and socialize together.[85]

Nationwide, the 1950s ushered in an era of conservatism, punctuated by the growing Red Scare. During this time, government-sanctioned anti-communist propaganda led to the “Lavender Scare,” a purge of gay and lesbian government employees. In the 1950s and 1960s, approximately 1,000 individuals were forced out of their jobs in the State Department; some were suspected of communism, but the majority were alleged homosexuals.[86] Those arrested were often outed in newspapers and other publications, and queer-identifying people were forced to hide in plain sight, socializing discretely and in coded language.[87]

By comparison, Boston and other urban centers offered queer community and a degree of personal freedom in the mid-20th century; at the same time, same-sex sexual activity remained illegal in Massachusetts until 1974, and police regularly raided gay bars, cruising areas, and private homes. Faced with discrimination, exclusion, and violence, queer people began to organize. During this time, queer-led organizations like the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis established chapters across the country, including in Boston.[88]

In the 1960s, Boston’s queer community increasingly settled in the South End, drawn by cheaper housing than in Beacon Hill and Back Bay. While many rented, those with means began buying and restoring the neighborhood’s iconic row houses.[89] The neighborhood’s diverse and tight-knit community offered some insulation from the prejudices encountered in other areas of Boston.[90] Against the backdrop of the interconnected struggles for civil rights, gender equity, the anti-war movement, and countercultural phenomenon, Boston’s queer activists began organizing on a public scale. At the same time, while nodes of Boston’s queer community became increasingly safe spaces for queer people to live openly, many if not most were forced to live double lives, presenting straight in their work and worship communities, while keeping their social and romantic lives hidden.

The South End’s Villa Victoria–a community victory in the fight against urban renewal, led by Inquilinos Boricuas en Acción ("Puerto Rican Tenants in Action", or IBA)–became a hub for Boston’s Latine queer community in the 1970s. Often facing discrimination in Boston’s predominantly white gay bars, queer Latine residents of Villa Victoria were known to host inclusive parties where all LGBTQ+-identifying people were welcome. In the next decade, the Hernandez Cultural Center opened in Villa Victoria; the center would go on to host many AIDS fundraisers.[91]

Bars, bookstores, and social clubs catering to queer clientele proliferated in the South End and Bay Village during the latter half of the 20th century. Among these were the Elbow Room (1975-1983), Fritz (1983-2013), The Boston Eagle (1970s-2021), Cherrystone Club (established 1975; today functions as the Trans Club of New England), We Think the World of You Bookstore (1990s - early 2000s), and Club Cafe (1990s - present).[92]

The Combahee River Collective (CRC) was founded in 1974 in Boston’s South End during a heightened time of racist violence in the city. CRC members were Black feminists and lesbians committed to the liberation of all oppressed people, with a focus on issues faced by Black and LGTBQ women locally. The Collective’s name was a nod to the 1863 Combahee River Raid, led by Harriet Tubman to free 750 enslaved people. CRC worked alongside the Committee to End Sterilization Abuse in Boston to fight against the sterilization of Black women and for abortion rights.[93]

In Boston, as in the United States as a whole, the queer community was rocked by the HIV/AIDS epidemic. For the first few years of the epidemic, outbreaks seemed isolated to a few cities, but by 1985, the virus had reached Boston. Its high mortality rate, early lack of treatment, and notably its prevalence among gay and bisexual men and trans women meant that those stricken with the disease experienced stigma and isolation, bolstered by fear and misunderstanding of the disease’s transmission. Local and federal governments were slow to act, and most hospitals offered poor treatment.[94]

Faced with stigma and slow action by the medical community, queer activists and allies confronted the epidemic locally and nationally. In Boston, groups like the AIDS Action Committee of Massachusetts, Inc., the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP / Boston), Boston Living Center, Fenway Community Health Center, Positive Directions, Inc., and the Multicultural AIDS Coalition pushed for the development of treatments; educated members of the public and the healthcare community about the virus and strategies for prevention; provided care and support for individuals affected by HIV/AIDS; and advocated for effective public health policy and funding.[95]

Even as the South End’s queer community rallied to support one another throughout the AIDS crisis, many began to migrate out of the city’s longheld “gayborhoods,” seeking cheaper housing and more open space in more suburban neighborhoods like Jamaica Plain, Dorchester, and South Boston. Since the 1980s, the neighborhood has once again faced a period of change, this time through gentrification: wealthy young families and single professionals have steadily moved into the trendy neighborhood, prompting rent hikes and an influx of businesses to accommodate new residents. Today, the South End holds onto its legacy as a diverse and culturally rich neighborhood, even as rising rent and property taxes and the persistent development of luxury housing forces longtime residents and community organizations to seek affordable accommodations elsewhere.

References

- Before Present (BP) years is a timescale used by archaeologists, geologists, and others to indicate when events occurred before the origin of radiocarbon dating in the 1950s. Archaeologists use 1950 as the commencement year for the present epoch, in part because the nuclear testing that took place in the 1940s drastically altered the carbon in our atmosphere, making radiocarbon dating after that time unreliable. Here, we’ve used 12,000 BP; this means “12,000 years before the calendar year 1950,” which calculates to 10,050 BCE. K. Kris Hirst, "BP: How Do Archaeologists Count Backward Into the Past?" ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/bp-how-do-archaeologists-count-backward-170250 (accessed October 27, 2021).

- Joseph M. Bagley, A History of Boston in 50 Artifacts, (Lebanon, New Hampshire: University Press of New England, 2016), 12-13.

- Russ Lopez, Boston’s South End: The Clash of Ideas in a Historic Neighborhood (Boston: Shawmut Peninsula Press, 2015), 3-4; Robert J. Allison, A Short History of Boston (Beverly, Massachusetts: Commonwealth Editions, 2004), 9.

- Bagley, 7.

- Lopez, Boston’s South End, 9.

- Lawrence W. Kennedy, Planning the City upon a Hill: Boston since 1630 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1992), 261.

- Ibid.; Boston College Department of History, “First Wave Immigration, 1820-1880,” Global Boston, accessed October 7, 2021, https://globalboston.bc.edu/index.php/home/eras-of-migration/test-page/.

- Nancy Seasholes, Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2018), 3-11, 13-17.

- Lopez, Boston’s South End, 24-25.

- Anthony Mitchell Sammarco, The Great Boston Fire of 1872 (Dover, New Hampshire: Arcadia Publishing, 1997), 7-8; “Great Boston Fire of 1872,” Boston Fire Historical Society, accessed October 27, 2021, https://bostonfirehistory.org/fires/great-boston-fire-of-1872/; “Notes from the Archives: The Great Fire of 1872,” Boston.gov, November 9, 2020, https://bostonfirehistory.org/fires/great-boston-fire-of-1872/.

- Lopez, Boston’s South End, 38; “A Storm of Cheap Goods: New American Commodities and the Panic of 1873 on JSTOR,” accessed October 28, 2021, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23045123; David Blanke, “Panic of 1873,” Teaching History, 2018, https://teachinghistory.org/history-content/beyond-the-textbook/24579.

- Lopez, Boston’s South End, 43.

- Robert Archey Woods, The City Wilderness; a Settlement Study (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, [c1898]), 52-57, accessed November 1, 2021, http://archive.org/details/citywildernessse00wood; Boston College Department of History, “The South End,” Global Boston, accessed November 1, 2021, https://globalboston.bc.edu/index.php/home/immigrant-places/the-south-end/.

- BC Department of History, “The South End,” Global Boston.

- Duane Lucia, “Exhibition: The New York Streets: Boston’s First Urban Renewal Project,” The West End Museum, 2021, accessed November 3, 2021, https://thewestendmuseum.org/exhibition-the-new-york-streets-bostons-first-urban-renewal-project/.

- BC Department of History, “The South End,” Global Boston.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., BC Department of History, “Syrians, Lebanese and Other Arab Americans,” https://globalboston.bc.edu/index.php/home/ethnic-groups/syrianslebanese-and-arab-americans/.

- Violet Showers Johnson, The Other Black Bostonians: West Indians in Boston, 1900-1950 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006), 56-60.

- Lopez, Boston’s South End, 91-93; BC Department of History, “The South End,” Global Boston.

- Robert Archey Woods, The City Wilderness: A Settlement Study (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and company, 1898), https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001743881, 84-85.

- Lopez, Boston’s South End, 49; Louise Carroll Wade, “Settlement Houses,” The Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago, 2005, accessed November 3, 2021, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1135.html.

- Lopez, Boston’s South End, 54; Elizabeth Lasch-Quinn, Black Neighbors: Race and the Limits of Reform in the American Settlement House Movement, 1890-1945 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 23-30.

- Inquilinos Boricuas en Acción records, M111, Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections. https://archivesspace.library.northeastern.edu/repositories/2/resources/877 (accessed January 19, 2022).

- Félix V. Matos Rodríguez, “Saving the Parcela: A Short History of of Boston's Puerto Rican Community,” in Carmen Teresa Whalen and Víctor Vázquez-Hernández, eds., The Puerto Rican Diaspora: Historical Perspectives (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2005), 206-07.

- Lopez, 168-170; Global Boston, https://globalboston.bc.edu/index.php/home/immigrant-places/the-south-end/; Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, “Boston’s Latinx Community History,” Boston’s Latinx Community History, 2022, https://latinxhistory.library.northeastern.edu/home/about; Inquilinos Boricuas en Acción records, M111. Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, https://archivesspace.library.northeastern.edu/repositories/2/resources/877 (accessed January 19, 2022).

- Betsy Klimasmith, "Race, Politics, and Public Housekeeping: Contending Forces in Pauline Hopkins's Boston," Trotter Review 18, no. 1 (Autumn, 2009): 6-22,127. https://link.ezproxy.neu.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/race-politics-public-housekeeping-contending/docview/198363065/se-2?accountid=12826.

- Lorraine Elena Roses, Black Bostonians and the Politics of Culture, 1920-1940 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2017), 32; Violet Showers Johnson, The Other Black Bostonians, 37.

- Psyche Williams-Forson, “Where Did They Eat? Where Did They Stay?: Interpreting Material Culture of Black Women’s Domesticity in the Context of the Colored Conventions,” in The Colored Conventions Movement: Black Organizing in the Nineteenth Century, (University of North Carolina Press, 2021), 62-71; Paul Groth, Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States, Berkeley: University of California Press,1994. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6j49p0wf/; Betsy Klimasmith, “Race, Politics, and Public Housekeeping: Contending Forces in Pauline Hopkins’s Boston,” Trotter Review 18, no. 1 (Autumn /Winter 2009 2008): 6-9.

- Lopez, 91-93; BC Department of History, “The South End”.

- Sarah Deutsch, Women and the City: Gender, Space, and Power in Boston, 1870-1940 (Oxford University Press, 2000), 19.

- Lopez, 93; Deutsch, 19; Lynne Potts, A Block in Time: A History of Boston’s South End from a Window on Holyoke Street (United States: Local History Publishers, 2012), 46.

- NAACP Boston Branch, “Branch History,” NAACP Boston Branch, 2019, http://naacpboston.com/branch-history/.

- Mia Michael, “‘A Home Away from Home’: The Women’s Service Club of Boston,” U.S. National Park Service, February 18, 2021, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/women-s-service-club-of-boston.htm.

- Zachary R. Dowdy, "NAACP Headquarters Building Faces Foreclosure Proceedings: [City Edition]." Boston Globe (Pre-1997 Fulltext), January 3, 1995, accessed November 22, 2021 https://ezproxy.bpl.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/naacp-headquarters-building-faces-foreclosure/docview/290726645/se-2?accountid=9675; “At 100, Boston NAACP Confronts City’s Mixed Past,” WBUR, January 15, 2011, https://www.wbur.org/news/2011/01/15/at-100-boston-naacp-confronts-citys-mixed-past.

- William Doherty and Alan Sheehan, "Court Takes Over South Boston High," The Boston Globe, December 10, 1975.

- Joe Pilati and Michael Frisby, "FBI, Police Probe 2 Firebombings," The Boston Globe, December 11, 1975.

- NAACP Boston Branch, “Branch History.”

- “The Great Migration, 1910 to 1970,” United States Census Bureau, September 13, 2012, https://www.census.gov/dataviz/visualizations/020/; “US Census Bureau, “Population of the 100 Largest Cities and Other Urban Places In The United States: 1790 to 1990,” Census.gov, accessed December 21, 2021, https://www.census.gov/library/working-papers/1998/demo/POP-twps0027.html; Richard Vacca, The Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places, and Nightlife, 1937-1962 (Belmont, Mass: Troy Street Publishing, 2012),134.

- Johnson, 2, 37.

- For more recollections of nightlife see interview with Gilbert White as part of the Lower Roxbury Black History Project. http://nb9662.neu.edu/roxbury/

- Vacca, 134.

- Ibid.; Lopez, Boston’s South End, 102, 119.

- Vacca, 134-137; Lopez, Boston’s South End, 119.

- Vacca, 136.

- “History,” King Boston, accessed September 15, 2022, https://kingboston.org/history/.

- Robert C Hayden, African-Americans in Boston: More than 350 Years (Boston: Trustees of the Public Library of the City of Boston, c1992), 85, 96; Vacca, 143-145.

- Vacca,179-189.

- Bill Beuttler, “An Oral History of Wally’s Cafe,” Boston Magazine, 2021. https://www.bostonmagazine.com/arts-entertainment/2021/01/19/wallys-cafe-oral-history/

- https://wallyscafe.com/history/

- Kevin Slane, “A historic South End jazz club has raised more than $35,000 for an ambitious new plan during the pandemic,” Boston.com, 2020, https://www.boston.com/culture/music/2020/06/12/a-historic-south-end-jazz-club-has-raised-more-than-35000-for-an-ambitious-new-plan-during-the-pandemic/.

- Vacca, 140-142; “One Musicians’ Union Where Once There Were Two,” Boston Musicians’ Association, 2021, https://www.bostonmusicians.org/about/history/one-musicians-union-where-once-there-were-two/.

- Potts, 67-68; Lopez, 105; James R Green and Robert C Hayden, “A. Philip Randolph and Boston’s African-American Railroad Worker,” Trotter Review Vol. 6 : Iss. 2 , Article 7 (September 21, 1992): 20–23.

- Ibid.; Willard Chandler, Interview with Willard M. Chandler, circa 1988-1989, interview by Robert C. Hayden, circa -1989 1988, University of Massachusetts Boston, Joseph P. Healey Library, Oral History Collections, Robert C. Hayden transcripts of oral history interviews, 1977-1991, https://openarchives.umb.edu/digital/collection/p15774coll11/id/126/rec/27.

- Altamont Bolt, “Interview with Altamont F. Bolt, 1988 October 22,” interview by Robert C. Hayden, October 22, 1988, University of Massachusetts Boston, Joseph P. Healey Library, Oral History Collections, Robert C. Hayden transcripts of oral history interviews, 1977-1991, https://openarchives.umb.edu/digital/collection/p15774coll11/id/114/rec/4.

- Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2017), 63-65; Robert K. Nelson, LaDale Winling, Richard Marciano, Nathan Connolly, et al., “Mapping Inequality,” American Panorama, ed. Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers, accessed January 6, 2022, https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/.

- United States. Federal Housing Administration, Underwriting Manual; Underwriting Analysis under Title II, Section 203 of the National Housing Act. (Washington, DC, 1934), 197-198, 378-379, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/002137289; Rothstein, 11-13, 64-67, 95-97.

- Bruce Mitchell and Juan Franco, “HOLC ‘Redlining’ Maps: The Persistent Structure of Segregation and Economic Inequality,” National Community Reinvestment Coalition, March 20, 2018, https://ncrc.org/holc/.

- Kenton, Bell, ed. 2013, “urban renewal,” Open Education Sociology Dictionary, accessed January 6, 2022, https://sociologydictionary.org/urban-renewal/; Ann Pfau, David Hochfelder, and Stacy Sewell, “Urban Renewal,” The Inclusive Historian’s Handbook, November 12, 2019, https://inclusivehistorian.com/urban-renewal/.

- Ibid.; John Blewitt, “Urban Regeneration,” in Encyclopedia of the City, ed. Roger W. Caves (New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2005), 483-486; Katharine Schwab, “The Racist Roots Of ‘Urban Renewal’ And How It Made Cities Less Equal,” Fast Company, January 4, 2018, https://www.fastcompany.com/90155955/the-racist-roots-of-urban-renewal-and-how-it-made-cities-less-equal; Digital Scholarship Lab, “Renewing Inequality,” American Panorama, ed. Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers, accessed January 6, 2022, https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/renewal/#view=0/0/1&viz=cartogram.

- Matthew Delmont, “Rethinking ‘Busing’ in Boston,” National Museum of American History (blog), December 8, 2016, https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/rethinking-busing-boston.

- Kerry Dunne, “Busing and Beyond: School Desegregation in Boston,” Digital Public Library of America, https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/busing-beyond-school-desegregation-in-boston.

- Lopez, Boston’s South End, 122-123; Duane Lucia, “Exhibition: The New York Streets: Boston’s First Urban Renewal Project,” The West End Museum, 2021, accessed January 7, 2021, https://thewestendmuseum.org/exhibition-the-new-york-streets-bostons-first-urban-renewal-project/.

- Massachusetts. General Court. House of Representatives, “1957 House Bill 1763. An Act Creating An Urban Redevelopment And Renewal Authority In The City Of Boston.” (1957), https://archives.lib.state.ma.us/handle/2452/301807; Boston Planning & Development Agency, “BRA History,” Boston Planning & Development Agency, 2021, http://www.bostonplans.org/about-us/bra-history.

- Lopez, 140-141; Mel King, Chain of Change: Struggles for Black Community Development (Boston: South End Press, 1981), 65-68; Boston Redevelopment Authority, “South End Urban Renewal Newsletter # 1, October 10, 1961,” 1961, http://archive.org/details/southendurbanren1961bost.

- Albert Boer, The Development of USES: A Chronology of the United South End Settlements, 1891-1966 (Boston: United South End Settlements, 1966), 40-44; Anthony J. Yudis, “644 Castle Square Relocations Big Job,” Boston Globe (1960-), April 25, 1964, ProQuest, https://ezproxy.bpl.org/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.bpl.org/historical-newspapers/644-castle-square-relocations-big-job/docview/366117295/se-2?accountid=9675; United South End Settlements records, M126. Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections. https://archivesspace.library.northeastern.edu/repositories/2/resources/910, accessed January 19, 2022.

- Nationwide, by the late 1960s, at least a third of a million families were documented as displaced due to urban renewal projects. Racial breakdowns of displacement were not consistently defined, they omitted information about immigrants and only documented families were eligible for relocation assistance. Because single adults were not eligible for relocation support, this data omits the staggering number of single adults displaced, including vulnerable populations like gay men.

- Digital Scholarship Lab, “Renewing Inequality,” American Panorama, ed. Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers, accessed January 6, 2022, https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/renewal/#view=0/0/1&viz=cartogram city=bostonMA&loc=12/42.3291/-71.0760&project=197; United States Department of Housing and Urban Development and United States Urban Renewal Administration, “Urban Renewal Project Characteristics” (Washington, D.C.: Urban Renewal Administration, June 30, 1962), https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000889434.

- BPDA Research Division, “Historical Trends in Boston Neighborhoods since 1950,” 2017, https://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/89e8d5ee-e7a0-43a7-ab86-7f49a943eccb, 8-9.

- Ann Pfau, David Hochfelder, and Stacy Sewell, “Urban Renewal,” The Inclusive Historian’s Handbook, November 12, 2019, https://inclusivehistorian.com/urban-renewal/; Mindy Thompson Fullilove, Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It (New York: One World, 2004), 14, 122-23.

- Lopez, Boston’s South End, 168-170; Global Boston, https://globalboston.bc.edu/index.php/home/immigrant-places/the-south-end/; Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, “Boston’s Latinx Community History,” Boston’s Latinx Community History, 2022, https://latinxhistory.library.northeastern.edu/home/about; Inquilinos Boricuas en Acción records, M111. Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, https://archivesspace.library.northeastern.edu/repositories/2/resources/877 (accessed January 19, 2022).

- Inquilinos Boricuas en Acción, “Let’s Build It: Annual Report 2020” (Inquilinos Boricuas en Acción, 2020), https://www.ibaboston.org/annual-reports.

- Lopez, 162-163; Mel King, Chain of Change: Struggles for Black Community Development (Boston: South End Press, 1981), 67-70.

- Janet Riddell, “A Carnival Flavor About Tent City,” Boston Globe (1960-), April 29, 1968.

- King, 111-118; “Activists Erect Tent City in Boston,” Mass Moments, accessed January 24, 2022, https://www.massmoments.org/moment-details/activists-erect-tent-city-in-boston.html; F.B. Taylor Jr., “Renewal Foes Camp in So. End Parking Lot,” Boston Globe (1960-), April 28, 1968; F.B. Taylor Jr., “South End Decision Left to Lot’s Owner,” Boston Globe (1960-), April 29, 1968.

- “Activists Erect Tent City in Boston,” Mass Moments.

- Lopez, Boston’s South End, 170.

- Tatiana Maria Fernández Cruz, “Boston’s Struggle in Black and Brown: Racial Politics, Community Development, and Grassroots Organizing 1960-1985” (Ann Arbor, University of Michigan, 2017), University of Michigan Library, https://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/140982, 98-101; “200 Notices Sent to Landlord,” Boston Globe (1960-), April 7, 1969; Viola Osgood, “Hub Rabbinical Court Fines Landlord $48,000,” Boston Globe (1960-), March 21, 1969; Viola Osgood, “Tenants Win Owners Rights In BRA Accord,” Boston Globe (1960-), August 12, 1969; Theodore Parrish, “Rabbinical Court Shows the Way,” Boston Globe (1960-), August 20, 1968; Charles Clark and Donald Ward, “A Fight to Keep 400 Residents in Their Homes in the South End,” Boston Globe, June 28, 2021, https://www.bostonglobe.com/2021/06/28/opinion/fight-keep-400-residents-their-homes-south-end/.

- Lopez, 171; Tenants’ Development Corporation, “TDC History,” Tenants’ Development Corporation, 2022, https://tenantsdevelopment.com/tdc-history/.

- “About Us,” Tenants’ Development Corporation, 2022, http://tenantsdevelopment.com/about-us/.

- Lopez, Boston’s South End, 191; Edward C. Burks, “Ford Signs Bill to Aid Housing,” The New York Times, August 23, 1974, The New York Times Archive, https://www.nytimes.com/1974/08/23/archives/ford-signs-bill-to-aid-housing-119billion-authorized-for-3-years.html; Gerald R. Ford, Statement on the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974, online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/256200.

- Michael Bronski, A Queer History of the United States, ReVisioning American History (Boston: Beacon Press, 2011), 156-60; Keegan O’Brien, “What LGBTQ Life Was Like Before Stonewall,” Teen Vogue, June 24, 2019, https://www.teenvogue.com/story/lgbtq-life-activism-organizing-united-states-before-stonewall.

- Ibid.

- Bronski, 176; Lopez, Hub of the Gay Universe, 165.

- Ibid.

- Bronski, 180.

- Ibid.; Lopez, Hub of the Gay Universe, 134-35; O’Brien, “What LGBTQ Life Was Like Before Stonewall.”

- Lopez, Hub of the Gay Universe, 134-35, 165.

- Russ Lopez, The Hub of the Gay Universe: An LGBTQ History of Boston, Provincetown, and Beyond (Boston: Shawmut Peninsula Press, 2019), 159.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 216, 226.

- The History Project, “Boston & Stonewall 50: Remembering, Celebrating, and Honoring Our Past,” StoryMapJS, 2019, https://uploads.knightlab.com/storymapjs/72526841f2384b2f30c3b514a37d4887/boston-stonewall-50-commemoration-locations/index.html.

- Tisa Anders, “Combahee River Collective (1974-1980),” BlackPast.org, April 23, 2012, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/combahee-river-collective-1974-1980/.

- David J. Sencer CDC Museum, “The AIDS Epidemic in the United States, 1981-Early 1990s,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/museum/online/story-of-cdc/aids/index.html.

- Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, “Collections: AIDS Action,” Boston’s LGBTQA+ History, accessed September 15, 2022, https://lgbtqahistory.library.northeastern.edu/aids-action/.